We have the pleasure to introduce to you Nick Lunch, an experienced Participatory Video facilitator, working at home in Oxford and over 30 countries for over 2 decades. Nick co-founded InsightShare with his brother Chris and has helped lead the organisation through an eventful journey of ongoing learning and evolution. Via Skype interview, we get to know him up close and personal.

King Catoy (KC): You are considered by many (including us at EngageMedia) as a pioneer in Participatory Video. Tell us the story about your journey. What led you to be an advocate of this methodology?

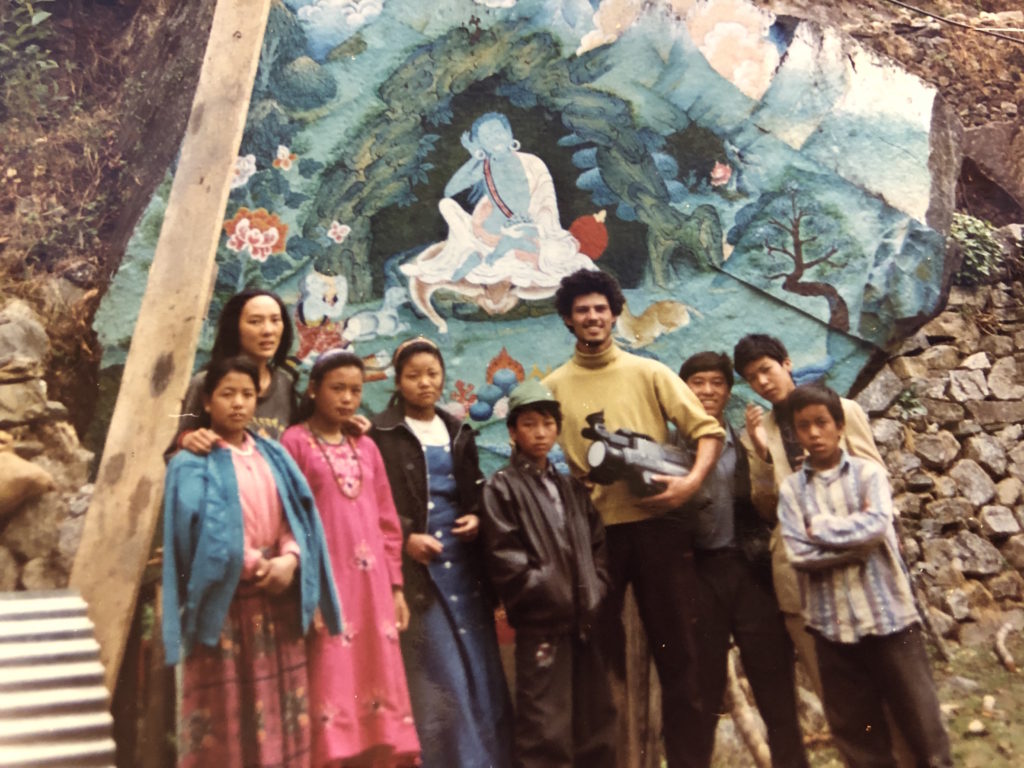

Nick Lunch: I started off as a self-trained filmmaker when I was in my 20s. I was an avid traveller. I’ve spent some of my formative years living in a remote community in Northern Nepal.

I really enjoyed that experience of being immersed in a very different cultural setting where I was the only Westerner. It rather forced me to interact and engage and make friends with local people! I went back there several times to understand that there are different ways of living in this world.

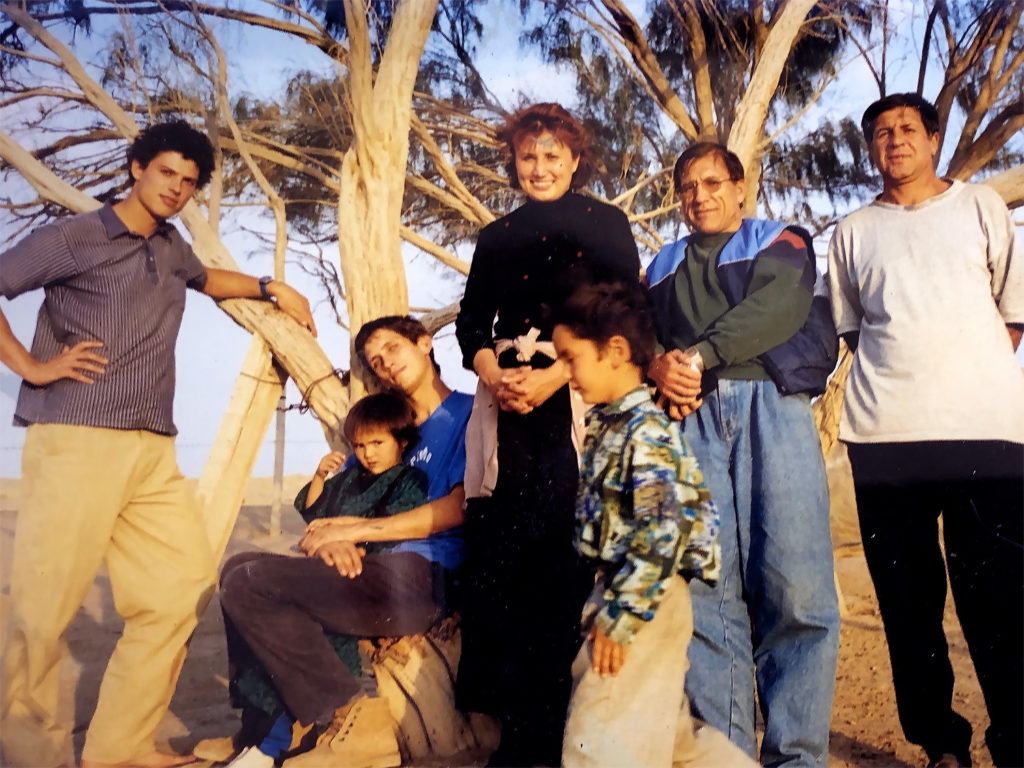

Nick Lunch with brother Chris on InsightShare’s first project in 1999, Karakum desert, Turkmenistan.

I just felt that I could go around the world travelling with my camera, having adventures, making lovely films about other people’s communities, other people’s way of life. But then, all I would be doing is just ventriloquising on behalf of those people; I’d be telling their stories for them; I’d be making my judgments. I’d possibly be sensationalizing certain aspects of their lives to make a good film, a good story. I wasn’t interested in doing that.

Even from an early age, I saw that I need to help amplify the unheard voices and the unheard stories. And I felt the best way to do that was to hand over the equipment, hand over the tools, share the skills with people. I’ve learned that local people are the real experts of their lives, so I help those people tell their stories themselves in the best way possible.

KC: Handing over the equipment from your hands to the community, was it a quick idea, or is this something that developed slowly?

NL: For my first two films I was the cameraman and co-director, but I worked in a very participatory way. The first film I made was in Kazakhstan in 1994. We were part of a film crew from England doing research and making a film about the search for identity in Kazakhstan after the collapse of the Soviet Union. I enjoyed handing the camera over so that people could watch the footage that we were filming through the tiny little screen. We were using these big Super VHS cameras then. Just seeing the smiles and laughter on people’s faces when they were watching themselves on the footage, I felt that was empowering for them, it was having a positive effect. I wanted to go further than that. Later I made a film in Nepal which was co-directed with a group of youth from the indigenous Yolmo people. Through that process, I learned to let go of control -a little bit!

But it wasn’t until I got back to England after that trip in 1996 and did a two-day course with ‘Real-Time Video’ in Reading in the UK who were pioneers of participatory video. It was there where I learned all the basic games – the name game, the disappearing game, etc. which we still use today. That set me on a different course and then my partner and I set up a charity in Oxford called -RAP – Right Angle Productions (RAP). From 1996 to 2001 we worked with kids from disadvantaged backgrounds who were excluded from schools or youth clubs because of behaviour issues and we could see them transform into community change-makers through the power of being involved in a video project – where they were in control. They were using the cameras, they were deciding what the topics would be that mattered to them, and then going out and interviewing adults in their community. In the process, they gained more respect from the adults and their videos acted as a catalyst for change. It just felt like a powerful process, so that was my apprenticeship in the participatory video!

Later we opened a drop-in centre for youth in Oxford, The RAP Yard. It was a place for them to feel comfortable, to get off the streets and be creative, to meet other young people from different cultural and ethnic backgrounds and work together on projects.

KC: Looking forward, in your years doing Participatory Video can you name one or two methodologies which worked?

NL: Yes, my vision has always been to support a network of local autonomous video collectives. Teams of local participatory video facilitators who can do what we do but they can do it locally and better because they understand the context. So a great example is the La Marabunta Filmadora video collective in Northwest Mexico that we’ve been working with for the past seven years. We helped to form the collective in the first place, providing them with equipment and funding. Then we trained them and gave capacity-building over multiple years. They are a group of Yaqui, Comcaac, Mayos, Guarijios, and Raramuri indigenous tribes from Northwest Mexico who are all very disconnected from one another. They are very marginalised, very much the bottom of the pile in terms of the way they’re treated by the state, by police and by non-indigenous people.

Video helps enable these groups to work together innovatively to combine their forces to note the similarities in their cultures, to understand that they have a common enemy in terms of defending their territories, defending their cultures.

That is for us a very positive experience to witness. La Marabunta Filmadora facilitators are mostly women, and they could overcome the challenge machoism, and convinced their husbands to become their biggest supporters. They are now offering participatory video training across Mexico to academic institutions professionally. They are earning livelihoods from participatory video and they are being invited into indigenous communities across Mexico and beyond to share knowledge, skills and based on a reciprocity agreement. Last month they trained Guajajara indigenous youth in Brazil who will use participatory video to defend their territory in the Amazon!

I could give you another example in Africa. We’re working with several tribes in Northern Kenya in the Lake Turkana region. The El Molo people are one of the most endangered cultures in Africa. They have almost lost their language. But they are creating video dictionaries to preserve what is left, and engaging youth in cultural activities as well as in conserving the dwindling fish stocks in the lake. I see an incredible shift on a personal level with people who get involved in our programs and who graduate to become facilitators – from where they start as participants in a project, often very shy, to growing into inspiring community leaders. Our trainees have access to video equipment, work in small teams, share their skills back with their communities, as they facilitate their projects.

We mentor our trainees over that process, and they come back together with one of our trainers to share the challenges they faced. Then we look at the videos together and offer some troubleshooting, and teach them how to edit, providing them with laptops.

Then in the second year, they start to facilitate more of their own projects and our involvement becomes less and less. I would say it completely transforms their lives. One of our trainee facilitators was a housewife, and now she has become a household name in her community; people come to her for advice. She has become a community leader that people respect.

Take the story we shared in the Video4Change Impact Toolkit, how video served to revive the growing of millet, and helped people to re-value the importance of traditional ecological knowledge. Wisdom Keepers who hold this knowledge need access to tools like the video to advocate to continue practising their ancient traditions. I believe if it is genuinely a video being made by the people for the people (i.e. participatory video), the audience will pay more attention, will trust it more, and some of them will take up those initiatives. Whereas if you have an outsider coming in to do it for them, then you have the danger of reconstructing something that is not authentic, or telling people how they should behave. And it is not just about who makes the video. At the community screenings, it becomes a real co-creative process – involves many people – not just one director or a small film crew.

Empowerment happens at these screenings. You can typically have hundreds of people there watching the footage and giving feedback, suggesting other people interview perhaps or checking facts. If something in the videos isn’t correct, then someone will notice that in the screening. So it is a way of triangulating the validity of the information, a way of getting the whole community behind what the film crew is doing.

KC: Cameras nowadays come in all forms and sizes, how do you see Participatory Video using these technologies?

NL: We have been noticing increased use of drones by our indigenous partners which they find useful as a way of seeing their territories and understanding their lands and resources. For example; seeing how the effects of water being stolen by the industrial agricultural complex in Sonora, Northwest Mexico is affecting the flow of the Yaqui River, the impact of pollution on children from spraying crops, or how impact of the illegal gas pipeline being forced through their territories, scarring the land and creating an unnatural division for wildlife and people.

Another example is using iPads instead of video cameras. iPads can be great in terms of the immediacy that you get seeing footage on that lovely screen as you’re filming and on immediate playback. It is really simple to do a little editing as well on the iPad using iMovie and you have the benefit of being able to go online for doing research etc. However, that might not work in some areas where the climate is very harsh and very dusty, windy and hot like in northern Kenya.

I think the problem with mobile phones, smartphones, is that they are very individualistic in design. They are used like someone’s Filofax or diary – a very personal object. It has all your contacts, all your details, so less natural to pass it on and share it with others. However, the surge in cheap communications like Whatsapp has also revolutionised our work and our ability to stay in contact with our partners.

KC: Imagine travelling back two decades to meet yourself just starting PV. What advice would you give?

NL: The advice I would give to a younger version of myself or someone starting up is to practice in your community! Do as much facilitation work in communities close to your home. Reduce the logistic challenges – make it as simple as possible. Offer your services for free and trust that the results will be so exciting and so powerful for the organisation or group that you are working with that more work will come from it.

Start building a portfolio through volunteering. Offer a very concise curriculum, say five sessions or ten sessions. Bring in the equipment and try to carry out a short PV process from beginning to end including right through to the screening process. It is at the screening you will feel that sense of collective celebration and achievement with the group you have been working with. You will start noticing the transformations in the individuals and will get a sense, a taste of what we call the “magic of PV”.

This is how I started and this kept me going through the difficult times when I was not able to earn a living from doing PV. But I was very passionate and had a very strong vision for what I wanted to do and what I felt PV could achieve.

King Catoy (2nd from right) and Nick Lunch (third from right) with other Video4Change Network Members at the South Africa Grassroots Gathering, October, 2019

This came from real experiences of using it on the ground in my community in Oxford with marginalised groups from around the city.

This is a methodology that has huge potential and it merits all of your attention and effort. It is a radical tool to challenge inequality. You have to gain a real belief in the method’s power because starting off is difficult.