We are human rights organisations using a tool to further our goals, the ethics is human rights. In that game we are not the only players; the players are those who suffer violations day in and day out, and they say: ‘we’re suffering and we want our stories out.’

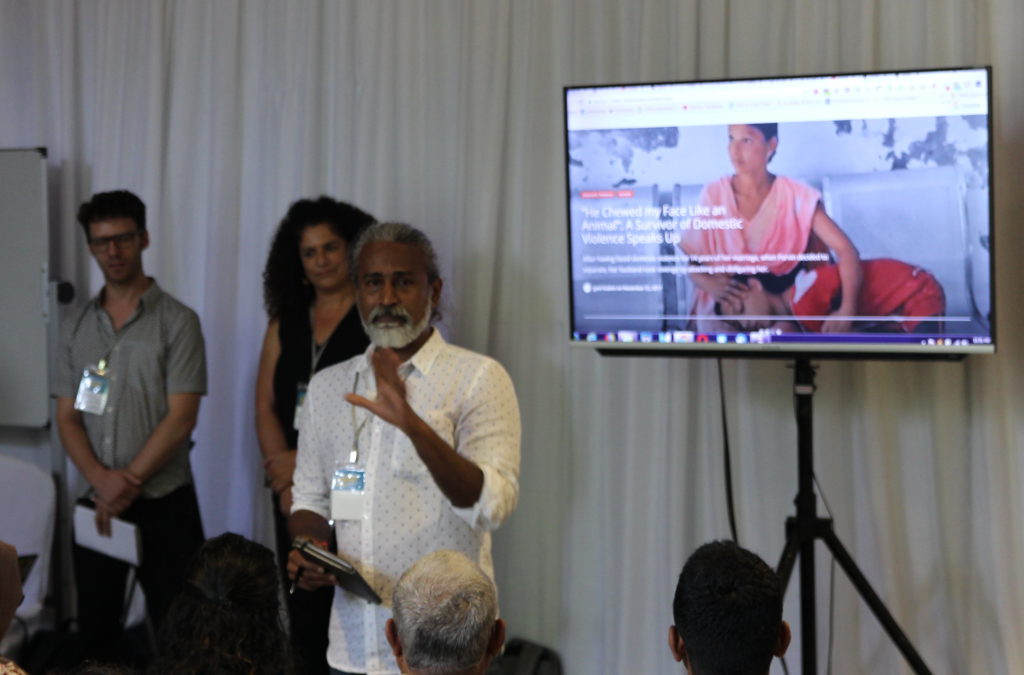

Image: ‘Video For Change’ panel explored community-based video storytelling. Photo by Raphael Tsavkko Garcia, used with permission.

(The article written by Elisa Marvena was originally posted in the Global Voices Summit 2017 page. Republished here under a CC license.)

The Video4Change team was present in the Global Voices Summit 2017, which took place during December 2-3, 2017 in the Sri Lankan Capital Colombo. The panel “Using Video for Change: Diverse Opportunities and Challenges” featured members of five organizations comprising Video4Change. Sam Gregory of Witness (moderator), Stalin K of Video Volunteers, Rima Essa of B’Tselem, Brenda Danker, of the Freedom Film Network, and Andrew Lowenthal of Engage Media.

Video4Change is a network of organizations that use video as a tool for marginalized communities to tell their own stories of resistance. They promote alternative narratives, defying the lack of diversity and representation of mainstream media, raising awareness about environmental and human rights violations and promoting social change. As Stalin K explained:

The diversity of mainstream media producers is deplorable so we decided that the only way to change the national discourses is to change the profile of the people who produce the content

But telling underreported stories can be a dangerous job, and these organizations have developed different strategies to protect their witnesses and volunteers working on the ground. In Palestine, for example, Rima Essa told us:

Everybody with a camera isn’t protected and can be arrested. Because they’re Palestinians. I can’t do anything for them but to pay high amount of money to release them, which is not always possible.

One of the strategies used by Video Volunteers is to provide their correspondents with identity cards from the organization, along with relevant documents they can use to introduce themselves to the authorities or security forces. Stalin K explained that these give volunteers protection in some areas of India, as armed men identify them as belonging to something “official”.

As for the Freedom Film Network working in Malaysia, being known and recognized by the community grants them validity, which becomes a safeguard from possible threats. Brenda Danker said:

We know the community and the community knows us. We screen everywhere: schools, community centres, in and out of Malaysia. Then it becomes more valid and it goes out to the press

Image: Video For Change drew a big crowd interested in community-based storytelling. Photo by Raphael Tsavkko Garcia, used with permission.

Sometimes the footage recorded may serve as proof in itself to protect correspondents from false charges. As an example, Rima Essa explained a fascinating story of a cameraman in Palestine who, when confronted by the security forces, managed to hide his camera’s memory card inside his mouth. After being recovered by B’Tselem, the footage was used in his trial to successfully get him released.

However, often proof of innocence is not enough. Volunteers on the ground generally operate under high risks and all five panelists stressed the importance of putting correspondents’ security first. As Essa said:

I always tell them: I don’t care about the camera, all I care about is your life.

Yet Stalin K spoke against adopting paternalistic attitudes, as the volunteers themselves choose to prioritize the value of the stories they want the world to know about. He said:

We are human rights organisations using a tool to further our goals, the ethics is human rights. In that game we are not the only players; the players are those who suffer violations day in and day out, and they say: ‘we’re suffering and we want our stories out.’